А вот,собственно,и полное подтверждение моим мыслям. Советник военного министра,майор Северский,произвел анализ разрушений и заключил,что в них нет ничего отличного от обычных зажигательных бомб. Естественно,все это было напечатано не потому,что он сомневался в том,что бомбардировка Хирошимы и Нагасаки была проведена атомными бомбами,а с точки зрения их неэффективности.

ИСТЕРИЯ АТОМНОЙ БОМБЫ '

Майор Александр П. де Северский

Автор "Победа Воздушной мощью" и т.д.

(Ридерз дайджест, февраль 1946 года, стр 121 до 126)

В качестве Специального консультанта военного министра, судьи Роберта П. Паттерсона, я провел почти восемь месяцев интенсивно изучая разрушения в Европе и Азии. Я тщательно ознакомился с каждым из разнообразных повреждений - от бризантных взрывчатых веществ, зажигательных артиллерийских снарядов, динамита, и их комбинаций.

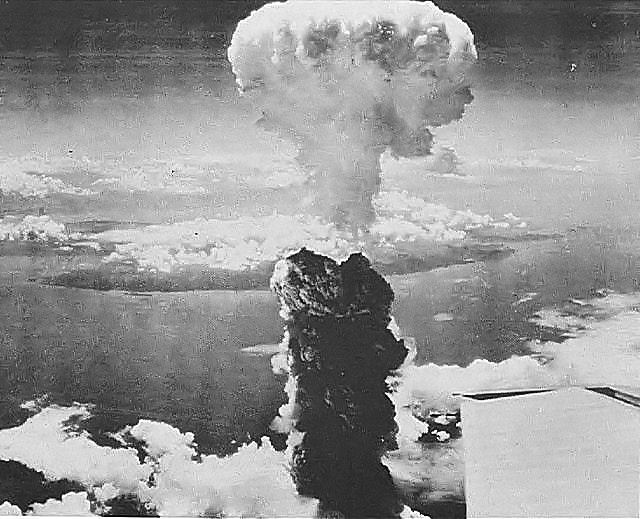

Во время этого исследования я осмотрел Хиросиму и Нагасаки, цели нашей атомной бомбардировки, исследуя руины, допрашивая свидетелей и принимая сотни фотографий.

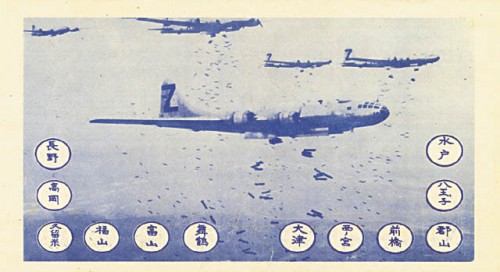

Это было результатом моего взвешенного мнения,сказал я корреспондентам в Токио, что последствия атомных бомб - не будущих бомб, но именно этих двух - были сильно преувеличены. При падении на Нью-Йорк или Чикаго, одной из этих бомб не было бы причинино больше вреда, чем десятью-тонным блокбастером; и результаты в Хиросиме и Нагасаки могли бы быть достигнуты около 200ми B-29 начиненными зажигательными бомбами, за исключением того, что были бы убиты меньше японцев. Я не "недооцениваю" атомные бомбы или оспариваю их будущий потенциал. Я просто передал мои профессиональные выводы о физических результатах двух бомб - и они оказались в поразительно отличающими от истерических версий, распространямых по всему миру.

.........

В Хиросиме я был готов к совершенно другому зрелищy. Однако, к моему удивлению, Хиросима выглядела так же, как все остальные города ,которые бомбардировали зажигательными бомбами.

Там пристуствовали знакомые розовые пятна, около двух миль в диаметре. Они были усеяны обугленными деревьями и телефонными столбами. Только один из двадцати мостов Хирошимы был поврежден. Скопления со современных зданий Хиросимы в центре города продолжали стоять вертикально.

Было очевидным, что взрыв не мог быть настолько сильным, как нас заставляли поверить. Это был обширный взрыв, но не интенсивный.

Я слышал,что множество зданий были поглощены мгновенно беспрецедентным жаром. Однако , здесь я увидел здания структурно нетронутыми, и более того, увенчанные неповрежденныму мачтами, молниеотводами, ,окрашенные перила, знаки предостережения воздушных налетов и другие, сравнительно хрупкие предметы.

На Т-образном мосту,который был прицельной точкой для атомной бомбы, я искал "лысину", где все предположительно должно было бы испариться в мгновение ока. Ничего подобного я там ,н в других местах не обнаружил. Я не мог найти никаких следов необычных явлений.

То, что я действительно увидел, было по существу ,копией Иокогамы или Осаки, или пригородами Токио - знакомые остататки деревянных и кирпичных домов, разрушенные неконтролируемым огнем. Везде я видел стволы обугленных и голых деревьев, сожженные и несгоревшие куски дерева. Огонь был настолько интенсивным, что согнул и скрутил стальные балки и расплавил стекло, пока оно не побежало, как лава - так же, как и в других японских городах.

Бетонные здания ,ближайшие к эпицентру взрыва, некоторые всего в нескольких кварталах от него, не обнаружили никаких структурных повреждений. Даже карнизы, навесы и тонкие внешние украшения были целы. Оконные стекла были, конечно разбиты, но все панельные рамы выдержали испытание на прочность; только оконные рамы из двух или более панелей были погнуты. Воздействие взрыва было абсолютно обычным.

Тогда я спросил множество людей, которые были внутри подобных зданий, когда бомба взорвалась. Их описания соответствовали множеству счетов,которые я слышал от людей, в бетонных зданиях, в районах, пострадавших от блокбастеров. Десяти-этажное здание прессовальных станков, примерно в трех кварталах от центра взрыва, был сильно опустошено пожаром, но в остальном невредимо. Люди, оказавшиеся в здании, не испытывали, каких-либо необычные ощущения.

Во больнице Хиросимы,большинство оконных панелей были выбиты,примерно в миле от центра взрыва. Потому ,что поблизости не было никаких деревянных конструкций она избежала огня. Люди внутри больницы не пострадали серьезно от взрыва. В целом ,эффект здесь был аналогичны тем, которые были бы получены в результате взрыва далекой тротилловой бомбы.

В общем,смерть, разрушения и ужас в Хиросиме были столь же велики, как и сообщалось. Но характер повреждений был ни в каком смысле не уникальным; ни взрывы, ни жара была настолько огромными, как принято считать.

ATOMIC BOMB HYSTERIA‘

By Major Alexander P. de Seversky

Author of “Victory Through Air Power,” etc.

(READER’S DIGEST, February 1946, pages 121 to 126)

As Special Consultant to the Secretary of War, Judge Robert P. Patterson, I spent nearly eight months intensively studying war destruction in Europe and Asia. I became thoroughly familiar with every variety of damage – from high explosives, incendiaries, artillery shells, dynamite, and combinations of these.

In this study, I inspected Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the targets of our atom bomb, examining the ruins, interrogating eyewitnesses and taking hundreds of pictures.

It was my considered opinion, I told correspondents in Tokyo, that the effects of the atom bombs – not of future bombs, but of these two – had been wildly exaggerated. If dropped on New York or Chicago, one of those bombs would have done no more damage than a ten-ton blockbuster; and the results in Hiroshima and Nagasaki could have been achieved by about 200 B-29’s loaded with incendiaries, except that fewer Japanese would have been killed. I did not “underrate” atom bombs or dispute their future potential. I merely conveyed my professional findings on the physical results of the two bombs – and they happened to be in startling contrast to the hysterical imaginative versions spread through the world.

My findings were pounced upon in outraged anger by all sorts of people, in the press, on the air, at public forums; and by scientists who haven’t been within 5000 miles of Hiroshima. But the violence of this reaction cannot alter the facts on view in the two Japanese cities.

I began my study of Japan by flying over Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, and dozens of other places. Later I visited them all on foot.

All presented the same pattern. The bombed areas looked pinkish – an effect produced by the piles of ashes and rubble mixed with rusted metal. Modern buildings and factories still stood. That many of the buildings were gutted by fire was not apparent from the air. The center of Yokohama, for instance, seemed almost intact when viewed from an airplane. The long industrial belt stretching from Osaka to Kobe had been laid waste by fire, but the factories and other concrete structures were still standing. On the whole it was a picture quite different from what I had seen in German cities subjected to demolition bombardment. The difference lay in the fact that Japanese destruction was overwhelmingly incendiary, with comparatively little structural damage to inflammable targets.

In Hiroshima I was prepared for radically different sights. But, to my surprise, Hiroshima looked exactly like all the other burned-out cities in Japan.There was a familiar pink blot, about two miles in diameter. It was dotted with charred trees and telephone poles. Only one of the cities twenty bridges was down. Hiroshima’s clusters of modern buildings in the downtown section stood upright.

It was obvious that the blast could not have been so powerful as we had been led to believe. It was extensive blast rather than intensive.

I had heard of buildings instantly consumed by unprecedented heat. Yet here I saw the buildings structurally intact, and what is more, topped by undamaged flag poles, lightning rods, painted railings, air raid precaution signs and other comparatively fragile objects.

At the T-bridge, the aiming point for the atomic bomb, I looked for the “bald spot” where everything presumably had been vaporized in the twinkling of an eye. It wasn’t there or anywhere else. I could find no traces of unusual phenomena.

What I did see was in substance a replica of Yokohama or Osaka, or the Tokyo suburbs – the familiar residue of an area of wood and brick houses razed by uncontrollable fire. Everywhere I saw the trunks of charred and leafless trees, burned and unburned chunks of wood. The fire had been intense enough to bend and twist steel girders and to melt glass until it ran like lava – just as in other Japanese cities.

The concrete buildings nearest to the center of explosion, some only a few blocks from the heart of the atom blast, showed no structural damage. Even cornices, canopies and delicate exterior decorations were intact. Window glass was shattered, of course, but single-panel frames held firm; only window frames of two or more panels were bent and buckled. The blast impact therefore could not have been unusual.

Then I questioned a great many people who were inside such buildings when the bomb exploded. Their descriptions matched the scores of accounts I had heard from people caught in concrete buildings in areas hit by blockbusters. Hiroshima’s ten-story press building, about three blocks from the center of the explosion, was badly gutted by the fire following the explosion, but otherwise unhurt. The people caught in the building did not suffer any unusual effects.

Most of the window panels were blown out of the Hiroshima hospital, about a mile from the heart of the explosion. Because there were no wooden structures nearby, however, it escaped fire. The people inside the hospital were not seriously affected by the blast. In general the effects here were analogous to those produced by the blast of a distant TNT bomb.

The total death, destruction and horror in Hiroshima were as great as reported. But the character of the damage was in no sense unique; neither the blast nor the heat was so tremendous as generally assumed.

In NAGASAKI, concrete buildings were gutted by fire but were still standing upright.

All of downtown Nagasaki, though chiefly wooden in construction, survived practically undamaged. It was explained that apparently it had been shielded from the explosion by intervening hills. But another part of Nagasaki, in a straight, unimpeded line from the explosion center and not protected by the hills, also escaped serious damage. The Nagasaki blast had virtually dissipated itself by the time it reached this area. Few houses collapsed and none caught fire.

All destruction in Nagasaki has been popularly credited to the atom bomb. Actually, the city had been heavily bombed six days before. The famous Mitsubishi plant was badly punished by eight high-explosive direct hits.

What actually happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki? There is little evidence of primary fire; that is to say, fire kindled by the heat of the explosive itself. The bomb presumably exploded too far above ground for that. If the temperature within the exploding area of an atom bomb is super high (and the effects in New Mexico tend to indicate that) then the heat must have been dissipated in space. What struck Hiroshima was the blast.

It was like a great fly swatter two miles broad, slapped down on a city of flimsy, half-rotted wooden houses and rickety brick buildings. It flattened them out in one blow, burying perhaps 200,000 people in the debris. Its effectiveness was increased by the incredible flimsiness of most Japanese structures, built of two-by-fours, termite-eaten and ry-rotted, and top-heavy with thick tile roofs.

The wooden slats of the collapsed houses were piled like so much kindling wood in your fireplace. Fires flared simultaneously in thousands of places, from short-circuits, over-turned stoves, kerosene lamps and broken gas mains. The whole area burst into one fantastic bonfire.

In incendiary attacks, people have a chance of escape. They run from their houses into the streets, to open places, to the rivers. In Hiroshima the majority had no such chance. Thousands of them must have been killed outright by falling walls and roofs; the rest were pinned down in a burning hell. Some 60,000, it is estimated, were burned to death.

Those who did manage to extricate themselves rushed for the bridges. There is reason to believe that one of the bridges collapsed under the weight of the frenzied mobs, although some maintain that it was brought down by the bomb blast. On the other bridges, the crush of hysterical humanity pushed out the railings, catapulting thousands to death by drowning. The missing railings were not wrenched out by the bomb blast as widely reported.

On a vast and horrifying scale it was fire, just fire, that took such high toll of life and property in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The victims did not die instantaneously in a sort of atomic dissolution. They died as people die in any fire. Quite possibly the blast was strong enough to cause internal injuries to many of those caught in the center of explosion; particularly lung injuries – a familiar effect of ordinary high-explosive bombing.

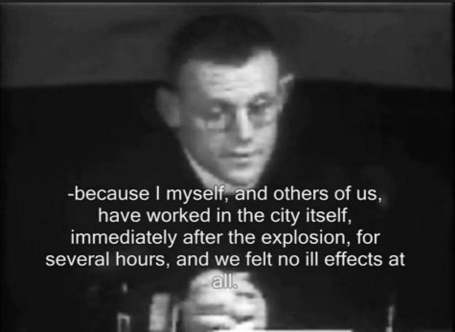

Perhaps there were some deaths from radioactivity. I met people who had heard of casualties from radio burns and radio poisoning. But I could not obtain direct confirmation. The doctors and nurses at the hospitals I visited had no such cases under their care, though some of them had heard of such cases. I also interrogated fire fighters and Red Cross workers who had rushed to the scene in the first few minutes. They all denied personal knowledge of any lingering radioactivity.

Such are the facts as I found them – they seem to me tragic enough without pseudoscientific trimmings. I am not alone in my opinions. Scientific observers on the spot to whom I talked in general shared my point of view. Nothing official came from the War Department to justify the wild exaggeration. It simply is not true that matter was vaporized in the intense heat – if steel had evaporated certainly wood would have done the same, and undamaged wood abounds everywhere in the rubble. In neither of the bombed cities was there a bald spot such as was created in the New Mexico experiment, and both atom-bombed areas have tree trunks and walls with growing vines to disprove the claims of super heat.

The more painstakingly I analyze my observations, indeed, the more convinced I am that the same bombs dropped on New York or Chicago, Pittsburgh or Detroit, would have exacted no more toll on life than one of our big blockbusters, and the property damage might have been limited to broken window glass over a wide area. Tue, the atom bombs apparently were released too high for maximum effect. Exploded closer to the ground, the results of intense heat might have been impressive. But in that case the blast might have been localized, sharply reducing the area of destruction.

Three scientists at the University of Chicago took me severely to task for saying 200 B-29’s with incendiaries could have done as much damage. They pointed out “that if 200 Superforts with ordinary bombs could wipe out Hiroshima as a single atomic bomb did, the same number of planes could wipe 200 cities with atomic bombs.”

These experts merely forgot to mention one detail – that the 200 cities should be as flimsy as Hiroshima. On a steel-and-concrete city high explosives would have to be added to the job. One atomic bomb hurled at Hiroshima was equal to 200 Superforts; but in New York or Chicago a different kind of atomic bomb exploding in different fashion, would be needed before it could equal one Superfort loaded with high explosives.

It seems to me completely misleading to say that the atomic bomb used on Japan was “20,000 times more powerful” than a TNT blockbuster. From the view of total energy generated, this may be correct. But we are not concerned with the energy released into space. What we are concerned with is the portion which achieves effective demolition. From that point of view, the 20,000 figure is reduced immediately to 200 for a target like Hiroshima. For a target like New York, the figure of 20,000 drops to one or less.

However, the comparison of the atom bomb with a TNT bomb, at this stage of development, is like comparing a flaming torch with a pneumatic drill. Everything depends on whether you’re trying to burn a wooden fence or demolish a concrete wall. All we can say with certainty is that the atomic bomb proved supremely effective in destroying a highly flimsy and inflammable city. It was one of those cases when the right force was used against the right target at the right time to produce the maximum effect. Those who made the tactical decision to use it in these cases should be highly complimented.

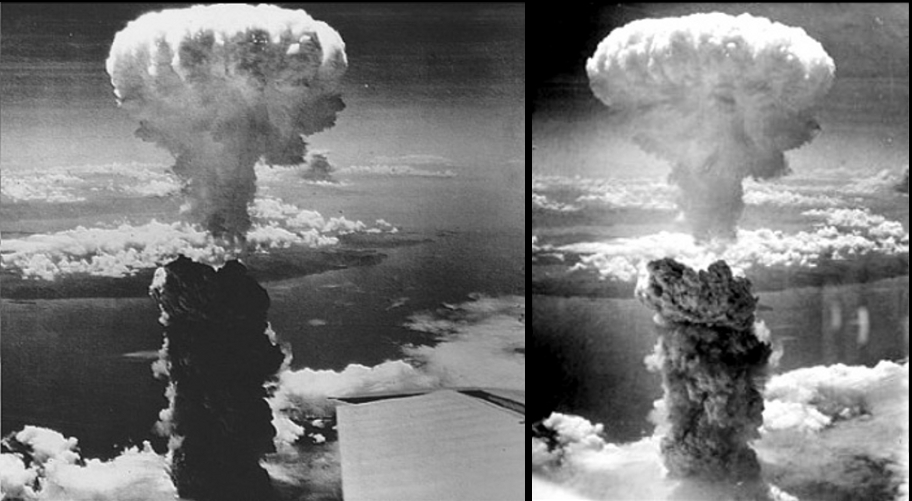

The bomb dropped on Nagasaki was said to be a great many times more powerful than the one dropped on Hiroshima. Yet the damage in Nagasaki was much smaller. In Hiroshima 4.1 square miles were razed; in Nagasaki only one square mile. The improved atom bomb, in other words, was only about one fourth as effective!

Why? There are various theories, but no one knows for certain. It underlines the fat that something besides additional mass will be needed to produce greater results on the target. Eventually, of course, the problem of obtaining maximum results from atom missile will be solved. Methods will surely be found for dissipating less of the released energy in space and directing more of it to destruction.

The Chicago scientists reminded me in their statement that “the bombs dropped on Japan were the first atomic bombs ever made. They are firecrackers compared with what will be developed ten or 20 years.”

That is exactly the point I am trying to make: that they are as yet in the primitive stage. Humankind has stampeded into a state of near hysteria at the first exhibits of atomic destruction. Fantasy is running wild. There are those who think we ought to dispense with all other national defence. They talk of a dozen suicides who will put on false whiskers, take compact atomic bombs in suitcases, and blow this country to bits. Such hyperbole is exciting, but it is a dangerous basis for national thinking.

On the size of the bombs, incidentally, there has been much uninformed rhetoric. How do so many people know that the atomic bombs weighed only “a few ounces” or “a few pounds”? After all, our biggest bomber, not a pursuit plane, was chosen to carry it.

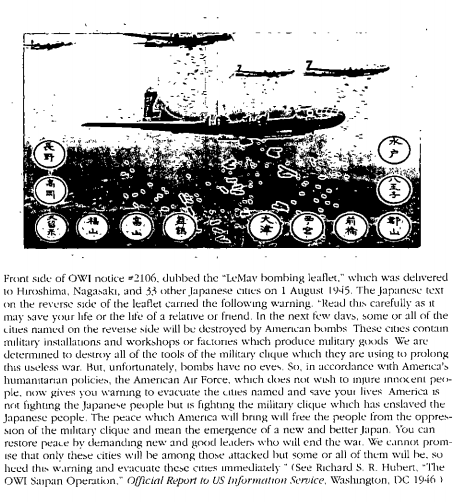

A conspiracy of circumstances whipped up atomic hysteria. The Japanese had every reason to propagate extreme versions. The atom bomb gave the perfect face saving excuse for surrender. They could now pretend that an almost supernatural element had intervened to force their defeat.

The BOMB provided a face saver for or leadership as well. Our leaders were deeply committed to invasion, insisting that there could be no victory without meeting the Japanese armies in traditional fashion. We were winning a victory over Japan through air power, but I am personally convinced that we would have gone through with the invasion anyway and paid the tragic and unnecessary cost in life. The momentum of the old assumptions was too great to be arrested.

The atom bomb instantly released everybody from past commitments. The nightmare of an invasion was cancelled, a miracle saving perhaps half a million American and several million Japanese lives. Though the Hiroshima and Nagasaki episodes added less than three percent to the material devastation already visited on Japan by air power, its psychological value was incalculable – for both the defeated and the victors.

The atom bomb fitted propaganda purposes. To isolationists it seemed final proof that we could let the rest of the world stew in its own juices – with our head start in atomic energy and our superior know-how, we were safe. The internationalists, on the other hand, tried to intimidate us by reminding us that we had no monopoly on science. Everyone could manufacture the atomic bomb, they said, and if we didn’t play ball we would be destroyed.

I am one of those who fought against inertia in the domain of air power. Consequently I am gratified that in relation to atomic energy the public is alert, that we are planning well ahead. But there is no call for the kind of frenzy that paralyzes understanding. Our only safety is in a calm confrontation of the truth.

I earnestly urge a cooling-off period on atomic speculation.

I am the last one to deny that atomic energy injects a vital and perhaps revolutionary new factor into military science and world relations. But I do not believe that the revolution has already taken place and that we should surrender all our normal faculties to a kind of atomic frenzy. Whatever we decide to do, let us do it calmly, logically and above all without doing violence to ascertainable facts.